Paleontologist Rodrigo Temp Müller reports the most recent discovery by CAPPA/UFSM: one of the most complete herrerasauridae dinosaurs known in history.

An almost complete fossil from a dinosaur that lived approximately 230 million years ago was recently found by researchers from the Center for Paleontological Research Support at the Federal University of Santa Maria (CAPPA/UFSM). The heavy rains that affected Rio Grande do Sul in May accelerated the erosive processes at fossil sites, exposing the bones of the animal, which was discovered in São João do Polêsine, near Santa Maria.

Below is the report by paleontologist Rodrigo Temp Müller, who coordinated the team responsible for the discovery of one of the most complete herrerasauridae dinosaurs known in history.

The team

Before starting the report, I would like to acknowledge those responsible for the discovery. Besides myself, this achievement also involved the participation of several others through field or laboratory work. They are: Fabiula Prestes de Bem, Lísie Vitória Soares Damke, Janaína Brand Dillmann, Mauricio S. Garcia, Jeung Hee Schiefelbein, Tamara Rossato Piovesan, and Vitória Zanchett Dalle Laste.

May 15 (Wednesday)

After a long period of heavy rains, they finally started to cease. We were anxious to begin the prospection work, anticipating that the significant amount of water would have greatly accelerated erosion at the fossil sites. This could potentially lead us to new fossils or destroy them if we did not rescue them in time.

In the early afternoon, we gathered our tools and equipment and set out with a team of five to our first stop, a site very close to the urban area of São João do Polêsine. This site is called Marchezan Site, where the complete skeleton of Gnathovorax cabreirai was previously found. This dinosaur belongs to the herrerasauridae group, which were apex predators. They had sharp teeth, long claws, and a bipedal posture. They were the first large-sized predatory dinosaurs, with some reaching up to six meters in length.

Now that you know how amazing the Gnathovorax cabreirai fossil is, you can understand why we always feel that we might find another similar fossil at this site. However, it was not the case this time. After meticulous scanning, we concluded that there were no other fossils to be collected at that moment. But the day would still surprise us.

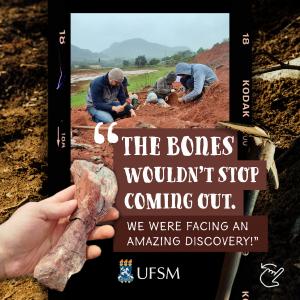

When we returned to the vehicle and proceeded to the next stop, it was already the middle of the afternoon. After traveling only 1.2 kilometers, we arrived at the Predebon fossil site. This is a rock exposure area from the Triassic Period, located at the edge of a dam visible from the road. At this spot, we had previously collected numerous Rhynchosaurus fossils, which are reptiles that lived alongside dinosaurs and are characterized by their snout-like appearance. After walking a short distance in the site area, I discovered some exposed fossil material. There was a kind of bone blade that was significantly damaged and a fractured cylindrical bone. Both were embedded in the rock, although they showed signs of erosion. We know that dinosaurs, unlike other animals from that era, had extremely thin bone walls, similar to that cylindrical bone. We all gathered around the find while a student and I began to partially expose the fossil remains. We were excited about the possibility of it being from a dinosaur, as they are rare components of the fauna from that time. Our excitement grew when we realized that the fragmented bone blade was part of the ilium, a bone of the pelvic girdle. Given our familiarity with dinosaur anatomy, it was easy to identify it as a part of the pelvic girdle associated with the leg bones of a herrerasauridae dinosaur, like the Gnathovorax cabreirai.

We found at the Predebon site what we had been searching for at a neighboring site! But it was too early to celebrate. The sun was beginning to set, and the forecast indicated rain. We could not remove the fossil materials at that moment as they were extremely fragile. It would be necessary to excavate the entire rock to transport them adequately to our research center. To protect the fossil that night, we applied a plaster layer. This would be enough to protect it temporarily, but we needed to continue the collection as soon as possible since we did not know if heavy rains might return. I do not know if all the team members dreamed about the fossil that night, but I am sure they could not wait to continue the work the next day.

May 16 (Thursday)

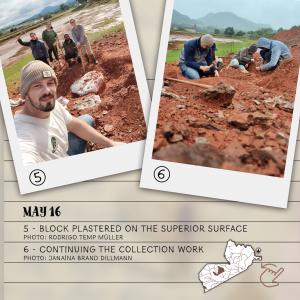

The day dawned cold with a light rain. It wasn’t the ideal condition for fossil collection, but we were dealing with unpredictable weather that could intensify into heavier rain at any moment. Therefore, we organized the necessary materials to continue the excavation and returned to the site. The plan was to excavate around the fossils to extract an entire block of rock containing them. After a few strikes with the pickaxe, more bone elements emerged. We were happy to see the quantity of bones from that fossil increasing, which meant we were likely uncovering a more complete skeleton. On the other hand, we would need to expand the excavation area to extract an even larger block.

While some team members focused on excavation, others continued searching for more fossils at the site. It didn’t take long for the students to announce a series of discoveries. Various more fragmentary materials of rhinoceroses were scattered in different spots. These fossils were collected and cataloged. Meanwhile, at the main collection point, bones kept appearing without pause. We were certain we had stumbled upon an incredible find. We could observe vertebrae, ribs, femur, tibia, and pelvic girdle bones. Due to the large volume of fossils, we had to proceed with great caution. In the more delicate areas, we used hammers and chisels to break the rock. In areas where the likelihood of finding more fossils was lower, we could use the pickaxe, which is a heavier tool. By late afternoon, the entire rock block was almost delineated. Before wrapping up for the day, we applied another layer of plaster over the new bone elements. The fossil was well-protected to await another night.

May 17 (Friday)

We returned in the morning to continue the excavation work. We were still excited about the discovery and hoped to finish extracting the rock block that day. We worked all day. Another smaller block with remnants of a rhynchosaur was completed, while part of the team continued breaking the rock around the block with the dinosaur fossils. Since the dimensions of the block were already outlined and the entire upper surface was covered with plaster, most of the work could be done with pickaxes. While one or two team members used pickaxes against the rock, others removed the debris with hoes. This process was repeated throughout the day.

Late in the afternoon, the block was completely outlined. Now we needed to plaster the remaining parts. We had the sun in our favor; it was a relatively warmer day than the previous ones, which made the plaster drying process faster. After repeating the plaster mixing process a few times and applying a cloth mixed with it around the block, we had the material fully protected for transport. It was at this moment that we faced the next challenge. When we rolled the rock block to apply plaster to the base, it became evident that we had something very heavy to carry. We would need a strategy to move the block to the truck’s bed. We decided to do this using a kind of stretcher made of wooden pieces and ropes. It was something we used frequently, but this block was a bit heavier than usual. Since it was already protected, we opted to leave the transport for the next day.

Before ending the workday, we prepared a makeshift stretcher at our research center. We didn’t know the exact weight of the block, but the team thought it would be important to conduct a “pilot test.” I, who weigh around 115 kilograms, ended up being the guinea pig. The group managed to lift me easily, and the stretcher held up perfectly. Not imagining that the block would be much heavier, we all went to rest to prepare for the final day of the collection.

May 18 (Saturday)

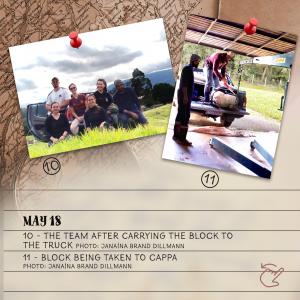

On that Saturday morning, the fossil skeleton would leave the spot where it had lain motionless for 230 million years. We parked the truck as close as possible to the location where the block rested. The first step in the transport work was to place the block onto the stretcher. During these initial movements, we realized that the task would be much more arduous than we had hoped. The block was much heavier than we had imagined; we now estimate that it weighed over 200 kilograms. As we lowered it onto the stretcher, we heard some creaking from the wood, indicating that it might break during the transport. One of the students on the team was assigned to secure the block with ropes to try to prevent any problems. Her experience as a scout always helps us in these moments.

The block was in position and securely tied to the stretcher. It was time to start the transport. We discussed a route that seemed the least uneven up to the top of the slope, where the truck awaited us. We counted to three and lifted the block together. We walked a few meters and then paused to reorganize. One of the wooden planks gave way, but we managed to continue. It took several moments until we finally managed to place the block in the truck’s bed. The achievement was celebrated with joy by everyone. We had successfully rescued the dinosaur skeleton!

May 20 (Monday)

On Monday, we returned to the Predebon site to search for elements that might have been left among the debris from the collection or even in the surrounding area. We also needed to continue collecting some remnants of a rhynchosaur that appeared next to the dinosaur we had already collected. To our delight, we found the dinosaur’s scapula and some phalanges still embedded in the rock. These materials were extracted and packed.

May 21 (Tuesday)

The next morning, we went to another site located in the municipality of Dona Francisca. Since we had spent the last few days collecting fossils in São João do Polêsine, we hadn’t had the chance to check other sites that had also been affected by the rains. At the location, we gathered some fragments scattered on the surface and also collected parts of a dicynodont that were exposed in the rock. Dicynodonts are very distant relatives of mammals. They are herbivorous, quadrupedal, and characterized by a pair of large tusks. We did not identify anything that required excavation. Therefore, we returned once again to the Predebon site in São João do Polêsine to collect some final materials.

In the afternoon, we finally turned our attention back to the block with the dinosaur. We were about to begin the “preparation” work. This involves exposing all the bone elements by removing the sediment covering them. First, however, it was necessary to cut through the plaster. After removing the plaster from the top, we transported the block to the laboratory and began a surface cleaning. Seeing that well-preserved fossil was incredible. Every student who passed by was amazed. Not only because it was a dinosaur with many preserved bones but also due to the quality of the preservation. We could see very delicate details of the bones.

But there was still something left to make us completely satisfied. Without a doubt, when studying vertebrate fossils, what attracts the most attention is the skull. It is through the skull that we get a glimpse of the “face” of the extinct creature. However, until that moment, we hadn’t preserved any parts of the skull. Of course, that alone would have been an incredible find, but paleontologists always have that feeling that there might be something under the next rock. That’s exactly what happened: as we removed the coarser sediment, pointed structures with serrated edges emerged. Teeth. The teeth that, 230 million years ago, frightened smaller animals and pierced the flesh of others less fortunate. Along with the teeth, the parts of the skull began to appear. Our discovery was complete. Everyone celebrated with enthusiasm. We were facing one of the most complete Herrerasaurid dinosaurs ever discovered in history.

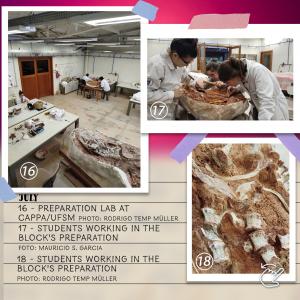

July

Since the discovery, we have identified almost all the bone elements in the block. Our research team has been working many hours on preparing the material. The sediment covering the fossil bones is slowly removed using scalpels, while a resin mixture is applied to the fossils to ensure their preservation. One of the most recent revelations has been the braincase region, which is intact. This portion will allow us to extract new information about the brains of the early dinosaurs.

Based on the size of the bone elements we have observed, we estimate that the dinosaur would have been around 2.5 meters in length, but it died before reaching its maximum size. We hope to remove all the bones from the rock over the next few months. After that, we will conduct comparative studies to determine the dinosaur’s species and gain a better understanding of how this predator lived in our region so long ago.

Funding

The research is funded by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq).

Text: Rodrigo Temp Müller, paleontologist at CAPPA/UFSM

Edition: Luciane Treulieb, journalist

Graphic art: Daniel Michelon De Carli, designer

Translation: Amanda Petry Radünz, assistant translator at the International Affairs Office of UFSM

Original publication: https://www.ufsm.br/2024/07/19/os-ossos-nao-paravam-de-surgir-estavamos-diante-de-um-achado-incrivel